THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES

and Hugo Friedhofer’s film score

Searingly poignant and joyously tender, William Wyler’s production of THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES remains a soaring testament to the sacrifice and heroism of “the greatest generation,” returning home to the uneasy reality they’d fought to preserve and protect.

Searingly poignant and joyously tender, William Wyler’s production of THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES remains a soaring testament to the sacrifice and heroism of “the greatest generation,” returning home to the uneasy reality they’d fought to preserve and protect.

The country was at once grateful, and unforgiving in their welcoming of the troops who had given up their lives and dreams to fight on foreign shores. While none of the returning American soldiers had asked for thanks or for special treatment, there was a growing and lingering resentment among some who had stayed at home, embarassed by the privileges they’d continued to enjoy, while vicariously sharing a victory won by the blood and emotional scarring of others. Boys had grown to men on foreign soil. Now they returned to their own country as strangers in a strange land, gladiators humbled by the pain of readjustment to an often indifferent, mundane, and trivial existence.

The idea for Wyler’s often sensitive, frequently painful examination of disruption and eventual repair, came from a Time Magazine pictorial article (August 7, 1944), addressing the difficulties of returning American soldiers readjusting to normal life and experience. Author MacKinlay Kantor was so moved by the Time portrayal that he turned the stories into a novel called Glory For Me. Producer Samuel Goldwyn purchased the novel, and commissioned Pulitzer Prize winning screenwriter Robert E. Sherwood to translate the book into visual expression. The film, re-titled THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES, starred Dana Andrews as a valiant gladiator, tortured by memories of battle, returning to a world in which his identity and persona were defined by a demeaning earlier position as a “soda jerk” at a pharmacy in his small home town. Now, matured beyond his years, dissatisfaction with his previous life experience seemed, to many, pompous and pretentious. Fredric March was also featured as a former bank executive coming home to his loyal wife, Myrna Loy, and precocious young daughter, Peggy, played by the lovely Teresa Wright. The scene in which March returns to his apartment and family is as memorable as any in screen history. As he opens the door, he quiets the excited reactions by his daughter and son, wanting to surprise his wife who is washing dishes alone in the kitchen. As she calls out to her children in the other room “Who is it?,” her query is met with silence. She calls again…and then stops in mid sentence. She intuitively reacts to an instinctual recognition of the quiet emanating from beyond the door, and gasps aloud. Turning slowly from the kitchen, she faces her husband, returned from the war. Their silent embrace speaks loudly, and in heartbreaking volume, of the pain of separation and reunion.

The cast is rounded out by first time screen actor, and real life embattled war amputee, Harold Russell, Cathy O’Donnell as the sweet and innocent love (Wilma) he left behind, and Hoagy Carmichael. Among the most sensitive performances is, however, by character actor Roman Bohnen as Dana Andrews’ father, whose tears of pride overwhelm the screen with gentle, understated beauty, as he attempts to read aloud his son’s commendation for wartime bravery to his wife at their squalid kitchen table. His simple reading of the military citation, while fighting back tears, is a powerful, understated gem of screen performance, under the direction of Willam Wyler and cinematographer Greg Toland.

Perhaps the most compelling component of Wyler’s film, however, is its majestic musical scoring by Hugo Friedhofer. Arriving in Hollywood in 1929, Hugo Friedhofer quickly established himself as one of the screen’s most able and popular orchestrators, working closely with such composers as Erich Wolfgang Korngold and Max Steiner on some fifty motion pictures. In 1938, he composed his first full original score for Samuel Goldwyn’s production of THE ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO. He continued orchestrating scores for other composers. However, as his own reputation as a composer gained increasing stature, his availability as an orchestrator understandably decreased. In 1946, thanks to the enthusiastic intervention of Alfred Newman, Friedhofer was assigned the task of creating a score for THE BEST YEARS OF OUR LIVES.

From the first notes of music illuminating the main title sequence, one is struck by the rapturous eloquence of the score. It is pure Americana, a proud and majestic salutation filling the horizon with hope and promise for a glorious future. This was a new country, a new America reborn from the scarring and smoldering ashes of war, a land of unbridled optimism consumed by the joy of victory, and the limitless promise of tomorrow. The air was fresh and clean once more, and imaginations soared above the clouds. Freed from the bondage of war and depravity, a nearly childlike wonder and innocence permeated America. There was virtually nothing that we couldn’t achieve or become, now that the chains of ideological slavery had been excised.

Friedhofer’s score gently caresses the healing emotional wounds of Wyler’s troubled veterans. Particularly tender, both visually and musically, is the nearly heartbreaking scene in which Homer invites Wilma to witness the utter helplessness he experiences when undressing for the night, laying his hooks on the chair by his bed. The remnants of what had once been his arms and hands, reduced by explosions to ineffectual stumps, leaves him exposed, ashamed, and as vulnerable as a small child, seeking comfort and protection from his mother, in the terrified night.

The score explodes with rage as Fred Derry (Dana Andrews) revisits the corpse of a once noble aircraft awaiting demolition in the scrap yards. Sitting in the ghostly cockpit, the pain of battle returns in searing waves and nightmares, as phantoms of fallen comrades invade his recollections, and Derry remembers the horrific intensity of smoke, screaming comrades and machine gun fire poisoning the clouds around him. Regaining his composure, Derry leaves the skeletal remains of the fallen eagle, and his past, behind him as he is offered a job and, at last, a degree of personal cleansing and redemption.

As Homer finds love and compassion in the arms of his childhood sweetheart, marriage vows bring sanity once more to the children of catastrophe. Fred and Peggy embrace a similarly uncertain, yet loving future together, as Friedhofer’s music reaches glorious crescendo, while both America and her people prepare to rebuild the best years of their lives.

–Steve Vertlieb, 2007

More on Hugo Friedhofer —

I’ve read with interest some of the recent discussions and threads concerning the measure of Hugo Friedhofer’s importance as a composer, and it set my memory sailing back to another time in a musical galaxy long ago and far away. I have always considered Maestro Friedhofer among the most important, if underrated, composers of Hollywood’s golden era. His contributions to this lyrical art form have placed him high above most contemporary artists and musicians in my estimation and he will, perhaps,live on as one of the unsung immortals of film scoring.

I recall conversations with Miklos Rozsa regarding Friedhofer’s contribution to motion picture music forty five years ago. Rozsa found Hugo Friedhofer an enormously gifted composer who had contributed more to the world of music than he would ever know. Indeed, Friedhofer’s assessment of his own accomplishments was, to put it bluntly, derogatory and self punishing. Whenever the two spoke on the matter, Friedhofer would ridicule his own achievements and describe his career as miniscule and inadequate.

Friedhofer, as Rozsa discovered, lambasted the studio system and ridiculed his own significance within the industry. He had serious issues concerning his own self worth, and grew increasingly morose and cynical. He turned ever frequently to alcohol as a temporary cure for his depression and, during these bouts with feelings of inadequacy, became sadly impossible to reach. Rozsa told me that he had often tried to bolster Friedhofer’s sense of worth by commiserating with him, and reminding him of his many successes but that Friedhofer simply refused to accept his value and importance as an artist. Finally, it grew too painful to broach the subject. If Friedhofer felt more comfortable in his escalating self flagellation, there was little that Rozsa could do to lift him out of it. He couldn’t allow his own positive attitude to be pulled down by someone who could only continue to wallow in self pity and emotional suicide.

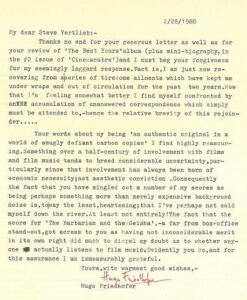

A year later, I decided to try to track Friedhofer down and attempt to repay the gift of beauty he had bestowed upon my life. I found his address and wrote him a long, loving letter of genuine admiration for his work and artistry. In late February, 1980, I received a reply written on an old, rickety typewriter. The page appeared stained with tears. The letter remains one of the most treasured pieces of correspondence that I’ve ever received. If I may, I’d like to share it with you.

–Steve Vertlieb, 28 November 2022

The letter from Friedhofer:

2/28/1980

My Dear Steve Vertlieb:-

Thanks no end for your generous letter as well as for your review of ‘The Best Years’ album (plus mini-biography, in the #2 issue of Cinemacabre’) and I must beg your forgiveness for my seemingly laggard response. Fact is, I am just now recovering from a series of tiresome ailments which have kept me under wraps and out of circulation for the past two years. Now that I’m feeling somewhat better I find myself confronted by an accumulation of unanswered correspondence which simply must be attended to,-hence the relative brevity of this rejoinder…..

Your words about my being ‘an authentic original in a world of smugly defiant carbon copies’ I find highly reassuring. Something over a half-century of involvement with films and film music tends to breed considerable uncertainty, particularly since that involvement has always been born of economic necessity; not aesthetic conviction. Consequently, the fact that you have singled out a number of my scores as being perhaps something more than merely expensive background noise is, to say the least, heartening; that I’ve perhaps not sold myself down the river. At least not entirely. The fact that the score for ‘The Barbarian and the Geisha’,- a far from box-office stand-out, got across to you as having not inconsiderable merit in its own right did much to dispel my doubt as to whether anyone actually listens to film music. Evidently you do, and for this assurance I am immeasurably grateful.

Yours, with warmest good wishes,-

Hugo Friedhofer

Never cease eating up anything to do with this film and score. Pop finally returned home from the Pacific a few months after VJ Day, tracked down the coed who was some other soldier boy’s date from that night whenever and married her November, ’46 in New York. Best Years opened up in Manhattan the next week!

Great to connect once again, Roger.

Best Years of our Lives Musical Score is one of the finest of all time. It did capture the America Moment post 1945 – uncertain future of return Vets with big problems that went by for so long unnoticed. Friedhofer’s score fit the movie and the times perfectly and your description is pretty near perfect. Friedhofer was a genius – thank you for this informative post.